Frank Zappa – Montreux 1971

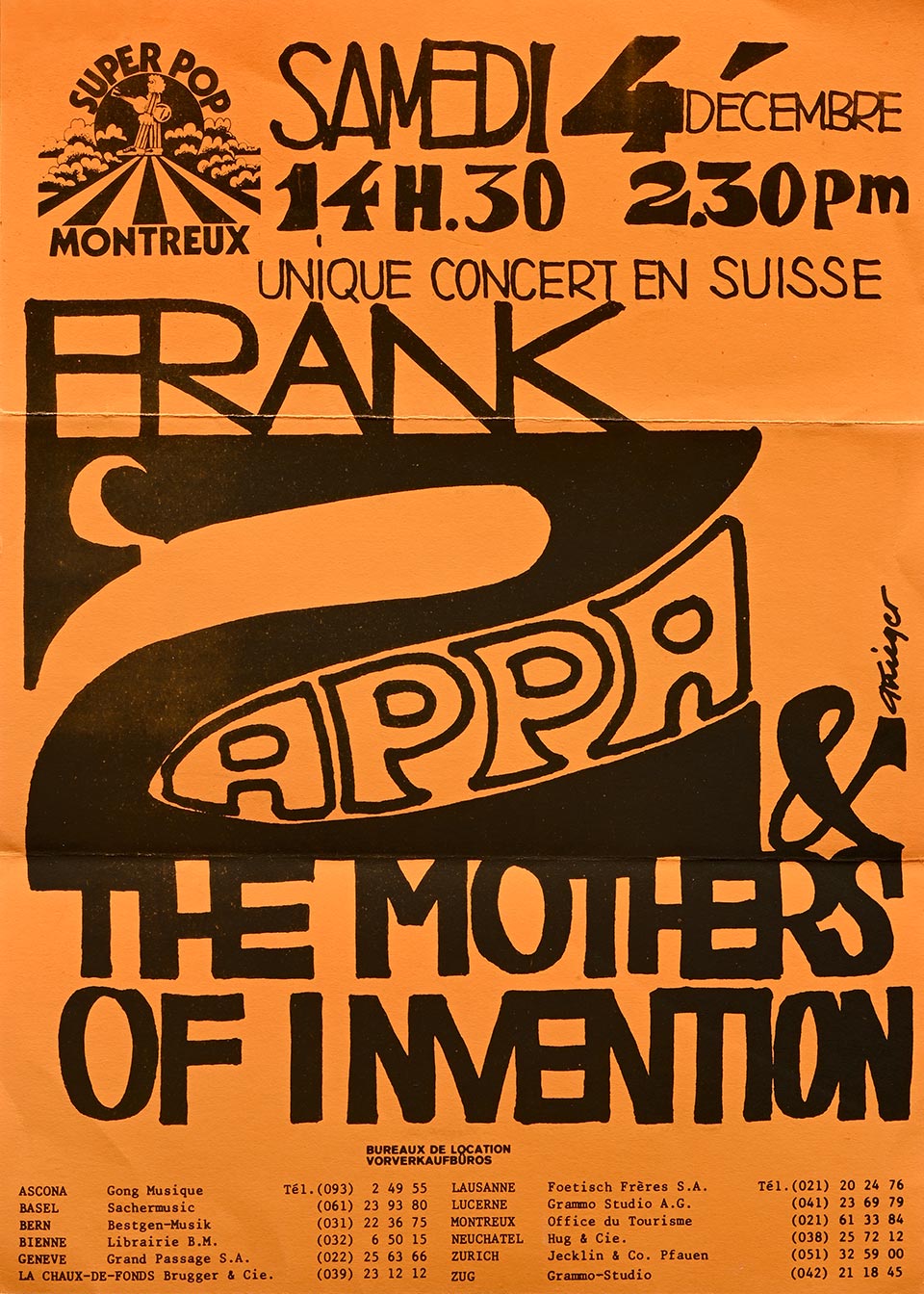

On Saturday, December 4, 1971, I took the train from Geneva to Montreux with a few friends to attend the Frank Zappa concert, which was scheduled for the afternoon—an unusual time for a rock concert: 2:30 PM.

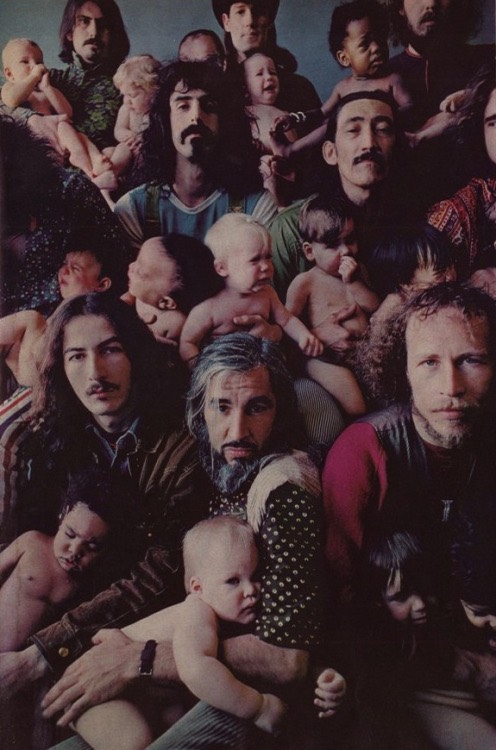

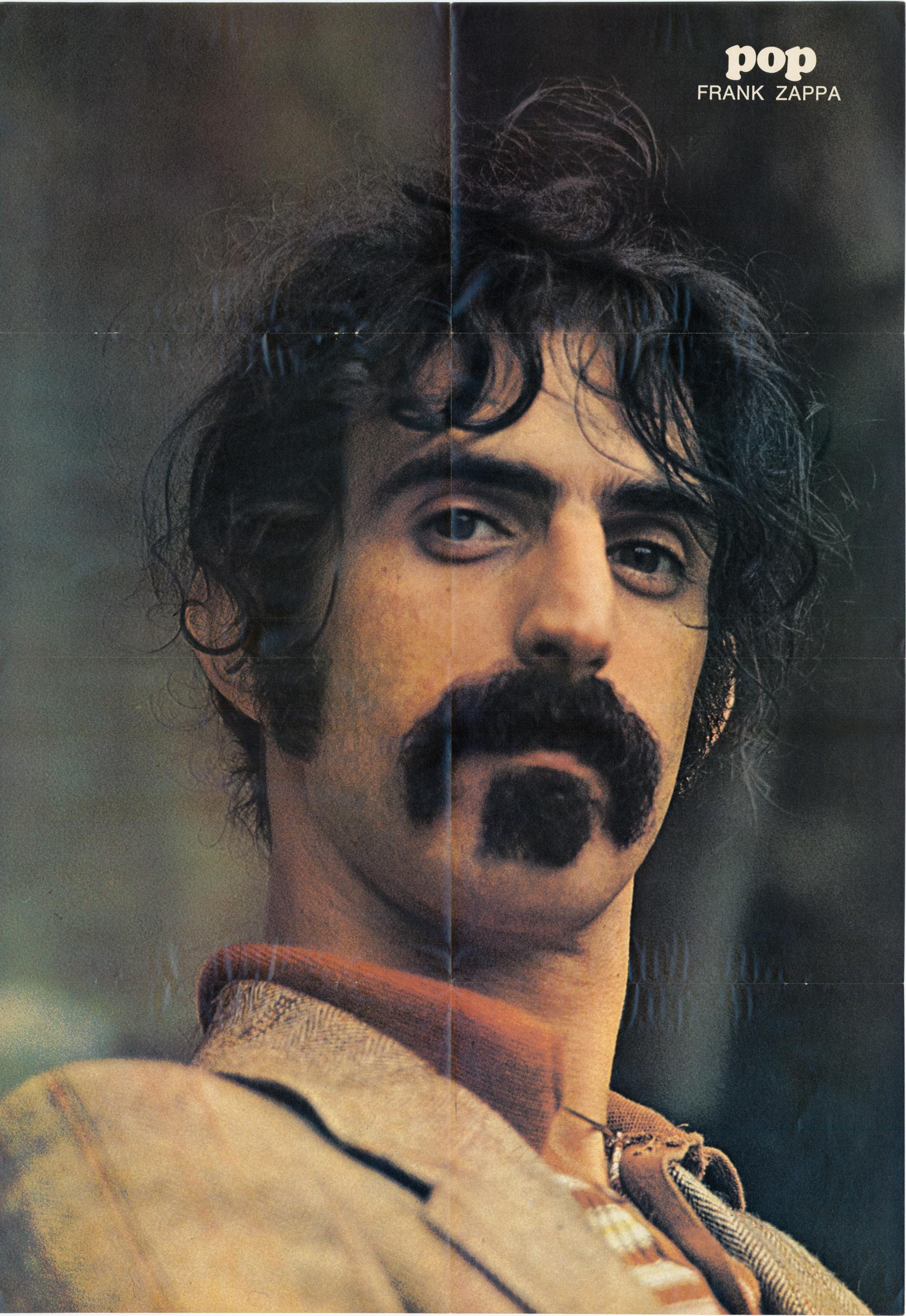

I had just turned sixteen, but I remember having photos of Zappa and the Mothers of Invention on my bedroom wall as early as the age of thirteen. In particular, I had cut out the famous photographs taken by Art Kane and published in LIFE magazine in 1968, in which they posed with babies—images that amused me greatly.

My first contact with Zappa was therefore more visual than musical, and I hadn’t seen any of his records in stores before the release of Hot Rats in 1970, which was the first of his albums to achieve real success in Europe.

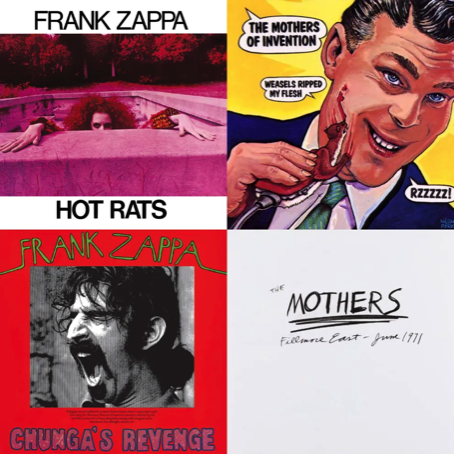

I was deeply struck by the music of Hot Rats, and by the time of the 1971 concert I also owned Weasels Ripped My Flesh, which someone had brought back for me from New York, Chunga’s Revenge, as well as Fillmore East – June 1971, which had just been released.

I had also seen Zappa on television in 1970 with Jean-Luc Ponty, as well as footage of his visit to the Amougies Festival, including his jam session with Pink Floyd.

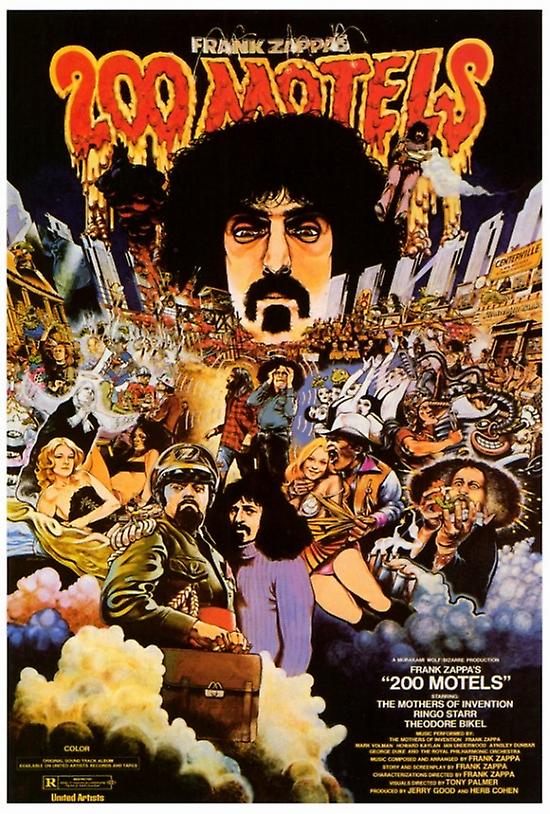

Leaving Montreux train station, we walked to the Casino. As we passed a movie theater, I caught sight of Zappa’s face on a poster. Stepping closer, I discovered it was an advertisement for the film 200 Motels, which I had never heard of before.

Intrigued, I assumed there would be a screening, but I didn’t take the time to look more closely, as we were eager to get to the concert venue. I told myself I would have time to look into it on the way back.

I believe a screening did take place that same evening, but after what happened during the concert, I obviously had other things on my mind.

I eventually had to wait until 1982 to see the film for the first time, when I was living in Los Angeles and 200 Motels was occasionally shown in one-off screenings at small cinemas.

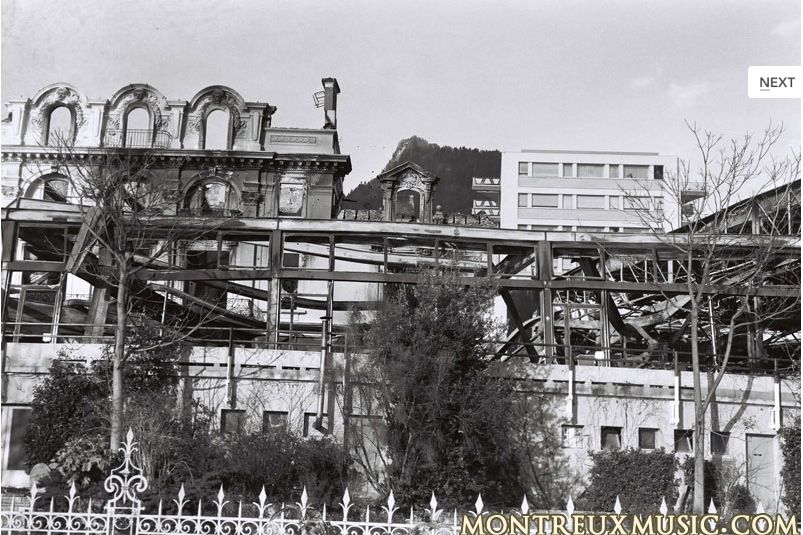

The Montreux Casino was an old building inaugurated in 1886. A modern hall had been built in the garden, attached to the main building on the lake side, to host concerts and other events. You entered it at ground level by walking through the old building, and because the land sloped gently toward the lake, the hall was at what Americans would call the second floor on that side.

On that day, scaffolding was on the old building, as seen in some photographs, probably for work on the façade or the roof.

This hall also hosted the Montreux Jazz Festival in the summer from 1967 onward. During the rest of the year, starting in 1969, rock/pop concerts were organized under the name Montreux Super Pop, once a month, attracting audiences from far beyond the region.

I was fourteen the first time I went there, in August 1970. There were two concerts scheduled, with three bands supposed to play twice each. I remember seeing Black Sabbath and Taste, but Cactus, the third band, was held up at the border and only played the second show, which I couldn’t attend.

Taste was the power trio led by Rory Gallagher, and their concerts were recorded, resulting in the album Live Taste.

Cactus's bassist was Tim Bogert, also known for his work with Vanilla Fudge, whom I had the pleasure of meeting in 1981, as he was teaching at the Musicians Institute in Los Angeles, where I was studying.

That day in August 1970, Claude Nobs was on stage announcing upcoming concerts, and that’s when he told us that Jimi Hendrix would be coming before the end of the year. The audience erupted with joy. It was the time when the triple LP and the film Woodstock had just been released, along with the album Band of Gypsys.

Unfortunately, Jimi died on September 18, 1970, not long after, and this deeply affected me at the time. I loved him and his music, and I was so looking forward to finally seeing him live.

1970 was an incredible period for musical discoveries. I remember other concerts I attended in the Casino hall: Deep Purple, Procol Harum, Jethro Tull and Santana, between 1970 and 1971.

I also remember missing bands I loved, such as Led Zeppelin and Chicago, as well as Santana’s very first concert there.

That day, December 4, 1971, I had just turned 16. I was already familiar with the venue: it was the fifth time I had entered this hall, not knowing it would be the last.

At that time, there were no chairs. Standing concerts were not yet in fashion, so the audience sat on the floor, sometimes on a cushion or on a rolled-up jacket, which was my case.

That day, there was an unusual decoration on the ceiling. It seemed tropical and colorful, made of rattan and paper flowers, most likely.

What is certain is that this material was dangerously flammable, as the future unfortunately proved. I don’t think the ceiling itself would have caught fire so easily without these temporary decorations, which do not appear in any of the photos I could find.

This decoration was probably intended for the holiday season, as the hall was also used as a nightclub or dance venue under the name Le Sablier (French for “The Hourglass”). It functioned as an extension of the concert hall, separated by a movable partition. Just before the entrance to the hall stood a notable decorative feature: a large hourglass containing 1,500 liters of colored glycerin.

In some photos, acoustic panels can be seen just above the stage, also highly flammable. They were perhaps made of bamboo, as one of the singers, Howard Kaylan, mentioned in his memoirs.

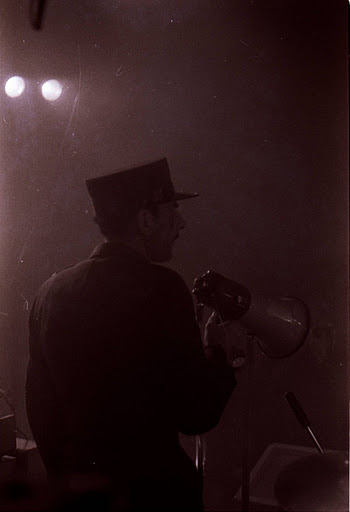

I remember Zappa coming on stage with a coffee pot and a cup on a tray. He was wearing a long coat that at first looked to me like a dressing gown, and apparently a nightcap with a pompom. I hadn’t remembered the nightcap, but it fits perfectly with the slightly absurd vibe I felt—and that I liked.

The coffee pot can be seen resting on the Orange amplifier head to Zappa’s right. The coat is casually draped over a WEM speaker cabinet, which would later be used to break a window.

At the time, I didn’t know all the pieces they were playing, I understood very little English, and this version of the Mothers included a lot of spoken dialogue. But I already knew the band’s sound from the recently released album, and I found it especially amusing to hear them play Happy Together in this context — the 1967 hit by the Turtles, the two singers’ previous band.

I remember that when Frank announced Call Any Vegetable with the famous introduction, “this is a song about vegetables, they keep you regular and they’re good for you,” the audience began to applaud—but all the lights instantly turned green, and the applause was cut short by surprise. When you listen to the concert recording, you can hear it very clearly.

After about an hour and twenty minutes, the band has just finished playing the theme from King Kong and gives way to Don Preston for a synthesizer solo. Don manipulates the oscillators of his Mini-Moog, producing sounds a bit like a siren—which, in hindsight, can seem strangely prophetic.

The end of the concert

I am sitting in the center, about two-thirds of the way back in the hall. The synth sound suddenly stops, and I see flames on the ceiling, about ten meters away from me, to my right.

Howard Kaylan shouts, “Fire! Arthur Brown in person!”—a joke referring to Arthur Brown, famous for his hit Fire and for performing with flames on his head. Then Zappa says, “Calmly go towards the exits, ladies & gentlemen.”

What people believe—though I didn’t see it myself—is that someone fired a flare gun toward the ceiling.

At first, the fire is very small. I think it will be put out quickly and that the concert will continue. My friends are already leaving the hall. I linger a bit before leaving, hesitating to leave my rolled-up jacket on the floor to keep my spot directly in front of the stage.

In my memory, people left the hall quickly but calmly through the back of the venue. I believe there were two exits. On the left side of the room, there was a small emergency door, guarded by a firefighter or a security officer. I remember that he was becoming impatient and urging us to evacuate more quickly.

At the time, I thought he was overly nervous and exaggerating, but in hindsight, I have to admit that he was right. It is likely that this is the man in uniform visible in this photograph, where he can be seen holding a megaphone.

The fire quickly spread to the ceiling. Spectators pulled back the curtains covering the large glass windows on either side of the stage. The windows ran from floor to ceiling and, as far as I remember, stretched across the entire width, possibly as a single pane. Along the right-hand wall of the hall were heavy chairs with high, rounded backs. I saw one of these chairs being thrown against the glass, and then others used amplifiers to smash the windows. I noticed a little blood: someone had been injured, but it seemed minor.

Once the windows are broken, a strong draft rushes into the hall, clearing the smoke but also feeding the fire very rapidly.

I decide to get out that way. The ground is about three and a half meters below. I’m in good physical shape, so I grab a ledge and drop onto the grass without any trouble. Not everyone would have found it that easy.

A friend—whom I didn’t yet know at the time—later told me this:

“Alain, I was there too! It was with one of the WEM speaker cabinets on the stage that, together with others, we smashed the windows, which allowed us to escape by jumping into the grass below…

I clearly remember Zappa very calmly telling the audience to leave without panicking. I think his calm made a quick and safe evacuation possible.

In the rush, I had left at my place a small Moroccan bag containing my belongings, along with an Afghan coat (sheepskin, very fashionable at the time), and above all my papers. Before jumping, I went back to retrieve them—they were exactly where I had left them.

Coming out of the smoke, a firefighter, visibly surprised to find me there, kindly asked me to leave quickly, because it was very dangerous to stay.

I had the impression that Don Preston’s ‘Moog’ was still producing strange sounds on the deserted stage… I grabbed my things and quickly exited through the shattered windows. It seemed to me that moments later, the ceiling collapsed.”

You can clearly see the WEM speaker cabinet at the far right of the stage, in one of the earlier photos, its three-letter logo is visible in the upper right corner, slightly blurred but characteristic of this popular English brand at the time.

The stage was very low, no more than about a meter high, which allowed another of my friends to climb onto it easily and end up going down a staircase behind the stage with Zappa.

Someone else had spent the concert leaning on the stage. He reached out and managed to grab Frank’s wah-wah pedal. Being a guitarist, he still uses it today, and it is probably one of the very few instruments to have survived the fire.

After jumping onto the grass, I watched the ceiling’s acoustic panels ignite and collapse all at once, making me fully realize what I had just escaped. The hall apparently went up in flames roughly thirty seconds after the last person had jumped.

I then walked around the building to find my friends, whom I had lost in the chaos.

Back at the front entrance of the Casino, I see people coming out through the main door holding Zappa posters that had been handed out. I have no idea that the old building is about to go up entirely in flames within minutes. So I go back inside and come out again with a few posters.

That same poster had appeared a few months earlier, folded into eighths, in a Swiss-German magazine called POP. The version handed out at the concert was the same size, but without a logo. It wasn’t folded, but printed on thin paper, none of those copies survived the years. I still own a folded copy from the magazine.

This door must have been on one side of the old building; the main entrance was larger than this.

Frank Zappa, wearing his coat.

A fairly large crowd had gathered outside. I remember that an alarm went off well after the fire had started, when everyone had already exited the building. Its late arrival caused a burst of laughter in the crowd.

It is said that the large hourglass near the entrance exploded. I’m not certain that I remember the sound of the explosion, but one can imagine that the 1,500 liters of glycerine it contained contributed to the extremely rapid spread of the fire through the main building.

The old building was completely engulfed in flames at nightfall, and it was truly impressive. I heard reports of flames reaching up to 50 meters.

I particularly remember the moment when the roof collapsed all the way down to the ground floor with a tremendous crash.

This photo, taken from the garden in the days following the fire, shows the area corresponding to the back of the stage.

I believe I held on to the ledge at the far left of the photo before jumping down to the left of the bushes.

This article tells the story of the event from the perspective of someone who was actually there. Over the years, I’d read or heard plenty of accounts of the fire—some more fanciful than others, and a few even claimed that Zappa had announced it with a laugh, which is just absurd.

A few days later, a friend gave me a cassette of the concert—terrible quality, but I listened to it over and over until I knew every note by heart. I kept diving into Frank Zappa’s music, but not exclusively—I’ve always been open to and fascinated by a wide range of musical experiences.

The band Deep Purple is associated with this event, as they were on site to record their new album. They were attending Zappa’s concert and witnessed the fire, which inspired the song Smoke on the Water, built on a simple riff and which became a worldwide hit a few months later.

Strangely enough, Frank Zappa also passed away on December 4, in 1993.

Most of the photos included here were found online, and I don’t know who took them. I hope they won’t mind, and I’d be happy to credit them if they ask.

Copyright © 2021 Alain Rieder - all rights reserved

Revised and updated in January 2026

• Read my account of Frank Zappa - Zurich 1973 (Wetzikon)

• Read my account of Frank Zappa – Basel 1974 (coming soon)

Bertrand Theubet, whom I met in Montreux in 1974, when he was working for Swiss television, shares his memories in 2026:

“Having attended the concert (I was there with my friend Denis Wyss, who handled the sound from the control booth set up in the middle of the audience facing the stage), I’m impressed by the accuracy of your account. Everything is there. We had — modestly, I admit — helped evacuate the venue and, outside, roll out the fire hoses from the first responders on site. I remember Claude Nobs trying to put out the flames by the pool. Your text brings back incredible memories. As for me, I never believed the theory that an audience member had fired a flare; I always suspected a short circuit in the ceiling’s electrical network. Thank you for your contribution.”

— BTh

PG, who was also present at the concert and is mentioned earlier in this article (wearing an Afghan coat), writes:

“A moment of rare intensity, described with great accuracy by my friend Alain Rieder.

I was there, so I can confirm that this account is accurate.”

Alain Rieder, December 1971

Alain Rieder is a professional drummer from Geneva, Switzerland. He attended Frank Zappa’s Montreux concert in 1971, witnessing the infamous Casino fire. Deeply influenced by Zappa’s music, Alain formed a band in the 1970s dedicated to performing Zappa compositions. Between 1971 and 1988, he saw Zappa live ten times, and once met him backstage. In 1981, Alain moved to Los Angeles to study at the Musicians Institute with Ralph Humphrey, one of Zappa’s former drummers. Frank’s music has had a lasting impact on his artistic journey.